Greetings. Last week, the Fed cut rates by 50 basis points. While this move shouldn’t surprise anyone following the bond markets—especially after Powell signaled readiness for a cut at Jackson Hole in August—the size of the reduction did catch many off guard. Out of 96 economists surveyed by Bloomberg, 93 anticipated a smaller 25 basis point cut (and while I am no economist, I said in my last journal that a 50-basis point cut was warranted). In this entry, I will address three pressing questions stemming from the Fed’s decision: 1) Are we already in a recession? 2) Can the 50-basis point cut stave off further deterioration in the labor market? and 3) What’s the outlook for future rate cuts? As always, thanks for reading.

Are we already in a recession?

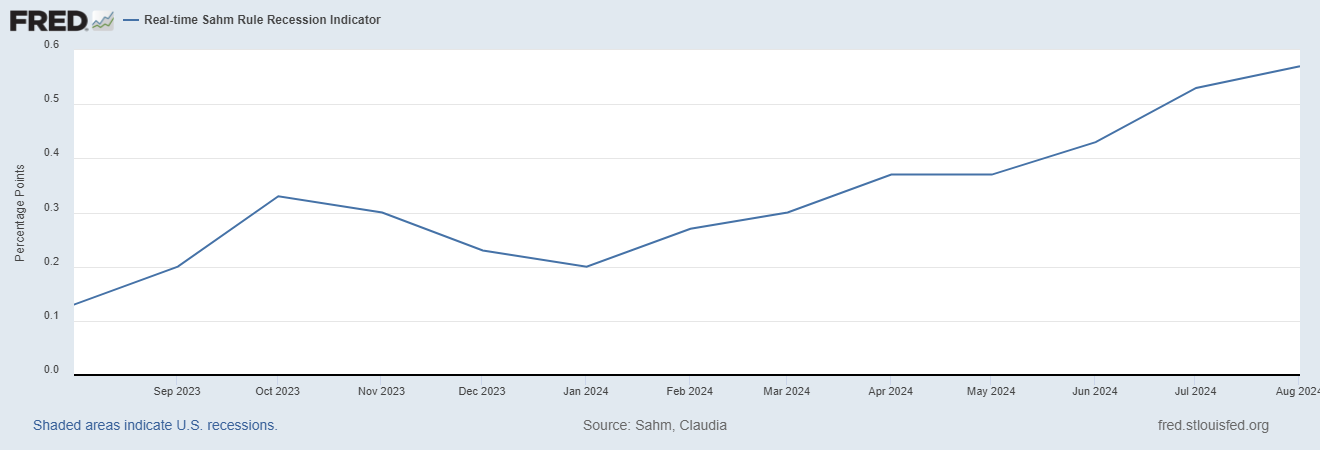

The discussion about whether the U.S. is already in a recession didn’t begin this month; it started two months ago when the so-called Sahm Rule was triggered. This rule states that if the three-month moving average of the national unemployment rate rises by 0.5 percentage points or more above its low from the previous 12 months, a recession has already begun. The rule has never failed to accurately identify recessions based on unemployment data going back to the 1950s. In July, the indicator reached 0.53, and in August, it further increased to 0.57 (see below).

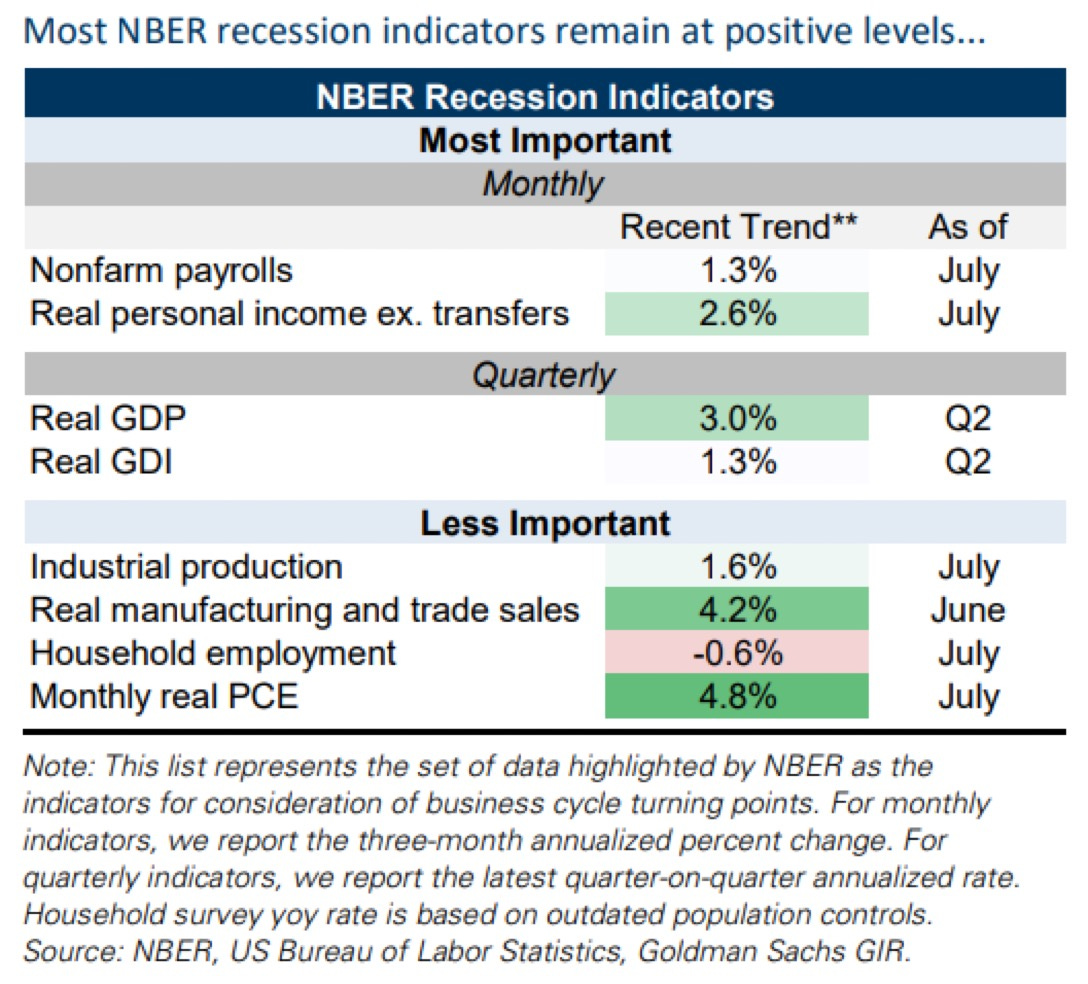

Nevertheless, Claudia Sahm, the economist behind the Sahm Rule, stated in a recent article in the NY Times that while the rule “has accurately forecast prior recessions, it and other economic rules of thumb are too simple for this complicated, post-pandemic time.” She argues that the U.S. is not in recession, nor is it even on the verge of one, with GDP projected to grow about 3% for the second consecutive quarter (source: NY Times). Goldman Sachs shares a similar view. As shown in their table below, most of the economic indicators that the NBER considers are at positive levels, suggesting that the U.S. is not in recession (the NBER is best known for its Business Cycle Dating Committee, which determines the official dates of U.S. recessions).

Source: GS

While I, too, believe that the U.S. might not be in recession (at least not yet), positive economic data has not prevented the NBER from declaring recessions in the past. More importantly, most recession indicators that the NBER monitors tend to deteriorate during a recession, not at the onset. For example, U.S. GDP was a solid 2% QoQ at the end of 2007 when the NBER declared the start of a recession (see below; the red shaded area indicates the beginning and end of the 2008/2009 recession).

Source: Bloomberg

In addition, another complication is that economic data often undergoes revisions, making macro analysis more of an art than a science. The chart below illustrates how Q1 GDP for 2001 was revised over time, revealing a staggering 3.3% difference between the initial estimate and the final figure:

Source: Bloomberg

Hence, while I don’t believe the US in a recession, I wouldn’t declare a soft-landing victory yet, as the economic “plane” is still descending and hasn’t landed. Only when the job market reverses its current downward trajectory can we confidently say we have achieved a soft landing - this is truly the trillion-dollar question.

Can the 50bps cut stave off further deterioration in the labor market?

As I wrote in Journal #9 (below), a soft landing is as rare as a unicorn sighting.

“History has not favored the optimists seeking a soft landing; since World War II, the US economy has weathered 13 recessions. How many soft landings has it experienced during the same period? Just one, if we exclusively consider a durable soft landing. This unique occurrence transpired after the 1993-1995 rate hikes without recession, leading to five years of sustained economic expansion until the 2001-2002 recession. It's this rare success that earned then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan the nickname ‘Maestro.’”

In my view, the 1993-1995 soft landing was made possible by a declining unemployment rate and the fact that the Sahm Rule never approached even the 0.25 level, which is half of the 0.5 recession trigger point (see below).

Today, the employment situation has been on a downtrend for quite some time, and the Sahm Rule trigger point of 0.5 has already been crossed; the recession train may have already left the station. Even with last week’s 50 basis point cut—and another 50 basis point cut projected by the Fed before year-end —I fear these measures may not be sufficient to prevent further deterioration in the labor market. Notably, the unemployment rate surpassed its 36-month moving average three months ago, and as I noted in previous journals, the uptrend in unemployment tends to accelerate once it crosses that threshold, much like a fire that feeds on itself, growing larger and more uncontrollable with each passing moment.

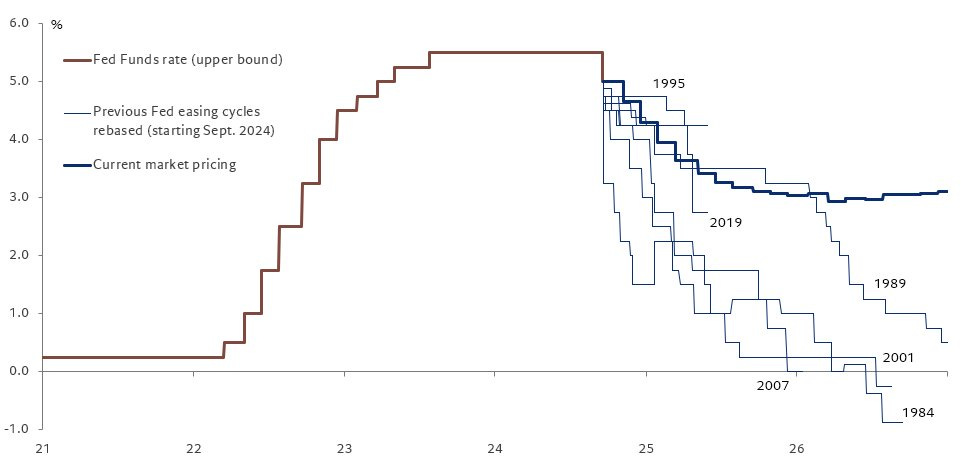

Moreover, as BCA Research has pointed out, past aggressive rate cuts in 1989, 2001, and 2007 did not prevent recessions from occurring (see below). Why should we expect a different outcome this time? Perhaps, as Claudia Sahm has argued, this time is different due to the complexities of our post-pandemic era. However, I believe that "this time is different" remains one of the most dangerous phrases in finance.

Source: BCA Research

Outlook for future rate cuts

What’s the outlook for future rate cuts? It largely hinges on your perspective in the trillion-dollar debate between a soft landing and a hard landing. If, like Claudia Sahm, you believe this time is different and that a soft landing is possible, then the current market pricing for rate normalization may play out as expected. Conversely, if we face a hard landing, the Fed will need to adopt a much more aggressive approach to rate cuts than their current forecast suggests. Frederik Ducrozet from Pictet effectively illustrates this with a graph shared on X (below).

Source: https://x.com/fwred/status/1836656018744307772

Given that most past rate cut cycles have coincided with U.S. recessions—namely in 1989, 2001, and 2007—the current market pricing of the rate trajectory stands on shaky ground if the unemployment rate continues to rise. The stakes in this debate are enormous, and the outcomes will significantly shape monetary policy in the months and quarters ahead as we find out the fate of the employment landscape.

So, what are the market-implied odds of a recession currently? According to Bloomberg/Macrobond, using SOFR option pricing, they sit at roughly 50% (see below). For what it’s worth, my (guess) estimate is closer to 60%. As always, thank you for reading.

Interesting that option pricing indicates an almost 50/50 at a hard landing, but the equities market seems to be much more optimistic. Additionally, shouldn't a 50-bps cut vs a 25-bps cut alarm investors more about the economy? My two cents is that the US market seems to be viewing every event as glass-half-full, which is understandable but dangerous given the strong equities' performance over the past 5Y.

Additionally, I'm sure you saw the PBoC "policy bazooka" that sent Chinese & HK indexes soaring. You previously mentioned a significant stimulus package was much needed. How do you view this introduced package? Could it be the inflection point in the economy, or did the market rally solely because of the national team's injection? Would love to get your opinion on this.

As always, thanks for doing this, it's always a pleasure to read.